Designing the advanced version of a forgotten game from the 80s, and making it 3D printable at home

For many years my tabletop-gaming friends and I have made the pilgrimage to Indianapolis for Gen Con, North America’s biggest tabletop gaming convention. Over 70,000 nerds from all corners of the world gathering for 4 days of wargaming, boardgaming, and roleplaying.

For me, Gen Con is all about one thing: the miniatures hall. Endless tables with scale miniatures in every possible variation: tanks, ships, planes, Napoleonics, battalion-scale warfare, wild-west shootouts, and more. The visual appeal alone is enough to bring me back year after year. Each game has its own complex ruleset refined after decades of convention play. My favorites are the entirely homebrew games, ones that were never published and are only played a few times a year at these large conventions.

One genre I find particularly fun to play is aerial combat. But one thing has always bothered me - these games almost always abstract away the height, reducing it to a simple number which is tracked. The terrain below is usually a painted mat, perfectly flat with no vertical height:

Another thing that bothers me is that movement and facing are often imprecise. Most aerial combat games use rulers or other guides to move the airplanes around, and rotations are particularly sloppy. There is often ambiguity about which aircraft are in line of sight of each other, and when multiple aircraft are close together it can be unclear which aircraft is in a particular location due to crowding:

And lastly, as much fun as it is to show up at Gen Con and be treated to games you cannot play anywhere else - wouldn’t it be great if you could play these special games at home with your gaming group?

What if there was an aerial-combat miniatures game that addressed these concerns, had convention-worthy visual appeal, and was 3D-printable by anyone?

During one of my regular game nights, a friend dug up a game from his childhood: 1988’s DragonLance. The goal is to fight other dragons in a race to complete a circuit around the map and capture the flag in the middle.

Although simplistic, the game was fun and implemented the fundamentals of what I was looking for: aerial combat with visually-represented height. The stacking of height tokens resulted in minimal height variations, but this was a significant improvement over the abstract number representations used in other aerial combat games. The dragon theme was unique and interesting, and the capture the flag objective was a fun way to ensure that players were forced into contact with each other (i.e. combat and movement are both guaranteed). The primary issue with DragonLance was that the aerial combat and movement were extremely simplistic; as we were playing I kept asking myself - what if this game had the refined movement and combat of the military aircraft games?

I had my target: a turn-based “capture-the-flag”-style aerial combat game with a dragon theme. And everything would be 3D-printable with a standard FDM printer.

The name of the game? That’s easy:

My design process encompassed the following:

One of the most fun and unique elements of aerial combat games is how movement is handled. A number of approaches have been taken:

One of the guiding principles of my game design was that movement and facing should be unambiguous. A hex-based system ensured that the location and facing of each dragon was restricted and visually obvious.

Another fun element of wargames is the tradeoffs/limitations of the different units available to each player. With a dragon theme I achieved this by distinguishing different types of dragons based upon their stage in a lifecycle:

Wyrmling - The youngest and smallest dragon. Quick but weak, with limited attack options.

Drake - A mature dragon. Moderately fast, moderately strong, with limited attack options.

Elder - A formidable dragon with considerable combat experience. Slow but strong, with full attack options.

Ancient - A legendary dragon. The largest, wisest, and oldest. Slow but extremely strong, with full attack options.

Using a hex-based system, I also avoided one of my biggest frustrations with most aerial combat games - crowding. By assigning small, medium, and large-sized bases for the dragon units, I subdivided a larger terrain hex to limit the legal dragon positions:

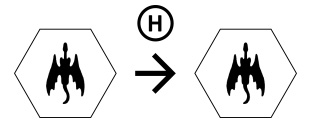

I also needed to ensure that dragon facing was unambiguous. I enforced this by only allowing dragons to face one of the 6 edges of the terrain hex:

For legal moves, I started by using the traditional aircraft movements.

Forward (F1-F3) - The dragon moves forward (in the direction it is facing) a total of 1, 2, or 3 hexes, with the maximum distance determined by the dragon type. The dragon’s facing does not change.

Left Shift or Right Shift (LS / LR) - The dragon moves into the hex located immediately forward and leftward (or rightward), without changing its facing.

Left Turn or Right Turn (LT / RT) - The dragon turns 60˚ counter-clockwise (or clockwise) in the current hex, before moving forward 1 hex (in the direction it is newly facing).

I decided against flying in reverse (it is hard to imagine a dragon doing that) but included a flip movement which spends a turn turning around.

Flip (F) - The dragon remains in the same hex, at the same height, but changes facing by 180˚.

Similar to a helicopter, I added a “hover” movement which allows a dragon to remain in the same hex by flapping its wings:

I wanted a fast-paced game, so I limited the amount of consecutive hovers - two hovers in a row is considered an illegal movement and results in the dragon falling and incurring some damage.

Dragons can go up and down in height, those moves are called Climb (+) and Descend (-).

Airplane games typically have complicated maneuvers such as the Immelmann turn, stall turn, barrel roll, etc. - but I was aiming for simplicity and kept things restricted to the movements listed above.

The following diagram summarizes all legal movement actions:

One of the most enjoyable aspects of movement in aerial games is the feeling of inertia and chaos. Since the games are turn-based, each player must make assessments of every other player’s likely next actions and future positions. Due to restrictions on the possible movements (for example, limits on how far a unit can rotate in one turn) a good player will often correctly predict where enemies and allies will end up. To increase the difficulty in doing this (and to give players a chance to escape), most games have players plot their movement for multiple turns at once - preventing immediately course-corrections. This adds an element of chaos which can be helpful when trying to confuse enemies or escape from a challenging situation - but also greatly increases the satisfaction of correctly predicting an opponent’s moves.

In DragonWars, players plot out movements for 3 turns at once - referred to as one Round.

Aerial combat games typically take one of two possible approaches to combat:

The first approach (non-plotted attacks) is a bit too easy in my experience, so for DragonWars I went with pre-plotted attacks (which rewards strategic thinking). Regardless of the approach taken, attacks usually deplete some limited resource (e.g. bullets, missiles).

I wanted a variety of attacks, so I went with three main types:

Fireball (F1-F5) - The Fireball attack launches a fireball 1 to 5 hexes forward (in the direction that the dragon is facing). The maximum range is determined by the type of dragon, and the fireball may be fired at any range less than or equal to this maximum. The fireball remains at the same height as the dragon that launched it. All dragons at that height in the targeted hex are hit. There is no effect on any other hex.

Fire Breath (FB2-FB5) - The Fire Breath attack launches a stream of fire which targets all hexes between the dragon and the target hex (in the direction that the dragon is facing). The maximum (and minimum) range is determined by the type of dragon. The stream of fire remains at the same height as the dragon that launched it. All dragons at that height in all targeted hexes are hit.

Close Blast (CB) - The Close Blast attack is a close range attack, targeting the three hexes immediately in front of a dragon. The Close Blast attack creates a wall of flames directly in front of the dragon, which extends from 1 height above the dragon’s current height, to 1 height below. In total, 9 hexes are targeted. All dragons at those heights in the targeted hexes are hit.

These three main attacks are the DragonWars version of the projectile, flamethrower, and explosive-style attacks found in other wargames.

Something fun in DragonWars which is not found in other aerial combat games is an opportunity attack between dragons that get too close to each other. This further discourages crowding and keeps players moving. It represents the dragons clawing or biting each other.

The following table summarizes all legal combat actions:

| Attack | Range | Area of Effect | Damage | Energy Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fireball | 1-5 | Targeted hex (at current height) | 4 | 1 |

| Fire Breath | 2-5 | All hexes between current and targeted | 4 | 2-5 |

| Close Blast | 1 | 3 forward hexes (-1,0,+1 of height) | 2 | 1 |

| Melee | 0 | Current hex | 1 | 0 |

The attacks available to each dragon are based upon the dragon type. In addition, each attack uses up limited energy:

| Dragon Type | Available Attacks | Energy Points |

|---|---|---|

| Wyrmling | Melee, Fireball (range 1) | 15 |

| Drake | Melee, Fireball (range 3), Fire Breath (2-3) | 15 |

| Elder | Melee, Fireball (range 3), Fire Breath (2-3), Close Blast | 15 |

| Ancient | Melee, Fireball (range 5), Fire Breath (2-5), Close Blast | 15 |

Each dragon has a health and energy level which is tracked and made visible to all players at the table. Players are able to assess the status of all dragons on the board during their plotting phase.

A series of ratcheting wheels was the initial solution:

Unfortunately after extended use the ratcheting mechanism loosened up too much, so an alternative approach using a slider was designed:

During the plotting phase, each player plots 3 turns worth of movement and combat actions for 4 dragons, in secret. At the end of the plotting phase, plotted actions are revealed to all players in a concise and easy-to-understand way. This is achieved by using a hex on the plotting board to visually distinguish the results of the various movement actions - the plotting board itself acts as a quick reference for where the dragon will end up after the plotted move. For combat actions, the various attacks are distinguished by the use of additional pegs (a line of pegs indicates a Fire Breath, as opposed to a single peg indicating a Fireball). After much experimentation I ended up with the following design:

When printed out at full-size for each player:

To plot actions, I designed a peg which is easy to print in mass quantities. Here is an example of a fully-plotted turn for a player, with movement and combat actions plotted for each of their dragons:

This plotting board design allows players to hide their plotting actions during the plotting phase by holding the board vertically, but once revealed (placed down on the table) everything is easily seen at a glance by all other players.

DragonLance had the players racing to the center of the map through checkpoints located on the opposite side of the board from their starting position. This arrangement ensured that players will come within range of each other, forcing a quick start to combat. DragonWars has a similar mechanic: players spiral towards the center of the map before capturing the “flag” and returning it back to their starting position.

As a dragon-themed game with strong visual appeal (with height being visually represented), there was an obvious solution: a tall mountain at the center of the map. A dragon egg (as the “flag”) is placed at the summit of the mountain. For more visual interest the mountain is surrounded by a forest, and the forest is surrounded by plains. Each player has a starting lair for their dragons’ initial positions. As a hex-based game this symmetry allows up to 6 players which is a good amount for a convention game.

The map (and the height of each terrain hex) was designed as follows:

The height of the mountain hexes requires players to spiral around the mountain to quickly gain as much height as possible on the way to the summit.

For starting positions, players have 3 hexes for their dragon lairs. Their Wyrmling starts on one of the field hexes just outside the lair, and inside the lair their Ancient occupies the middle hex. The player can place their Drake and Elder on the left or right hexes at their discretion:

For the size of each hex, I had a couple of considerations. I wanted the game to fit on a typical dining room table (a standard width of 36" to 40"), so that the game is still playable outside of a convention setting. And the hexes needed to be large enough to fit the dragon bases. A 3" diameter was the sweet spot:

3D-printed hexes of various colors were sufficient, but for a premium feel (and to maximize visual appeal at a convention) it would be ideal to use proper chipboard hexes with imagery on them. This was achieved at home rather easily with color printouts, spray adhesive, chipboard (0.05" thick) and cutting the chipboard to size (a 40W CO2 laser cutter was used, but any other cutting tool would have worked):

The 3D-printed terrain system is modular (to allow easy packing and unpacking) and flexible enough to allow custom maps if players want to try something different. I wanted a system which snaps together easily and allows for variable height at arbitrary locations. I also needed to keep in mind the required printing volume, as I do not expect everyone to have access to a large-format 3D printer. I stick with the dimensions of the extremely popular Ender 3 (220mm x 220mm x 250mm), as this was the most common entry-level FDM printer in the hobbyist community.

After various iterations I settled on the following modular components:

Assembly is simple:

I needed 4 types of dragons, representing 4 different life stages (increasing in size). The size of the hex constrained the size of the dragon bases, which gave a volume to work within. I wanted distinct silhouettes which are easily discernible on the gameboard. I kitbashed what was needed in 3dsmax.

Wyrmling:

Drake:

Elder:

Ancient:

The mounting platform mates up with the dragon bases to ensure dragons always have a legal facing. I added a marking line on each mounting platform to provide an additional visual indicator of the dragon’s facing:

Printing the dragon models on an FDM printer produced adequate results, but the higher resolution of a resin (SLA) printer would produce better results:

In addition to the dragon models, I designed an egg token with a simple attachment to the dragon which has captured it:

I needed a 3D-printable system for elevating dragons to their appropriate height. I wanted this height system to be modular and easily adjusted, ensuring heights are at discrete values of 1 to 9 units (with the possibility of extending higher if needed).

My initial approach was a stacking height riser:

This worked fine, but was cumbersome to use and slowed down gameplay. Inserting a new riser or changing the facing of the dragon both required removing and replacing the dragon (or one of the existing risers). One of my primary design goals was fast-paced gameplay, so to address this a telescoping solution was designed:

The bottom piece of the telescoping riser can be used similar to the previous stacking height riser, or the top may be removed and the telescoping feature added:

To enable easy changes in dragon-facing, the bottom of the telescoping riser has a ratcheting mechanism. This allows players to simply rotate the riser without removing it, and the ratcheting mechanism ensures that only legal facings are used:

This modular height system allows any required height to be achieved in a stable and consistent way:

UPDATE: This height system works great and enables fast gameplay, but after extended playtesting (as players became more comfortable with the game and its rules) an even faster height system was desired. A speedier system was designed, based upon standard 2mm carbon fiber rods (commonly used for RC planes and other DIY hobby purposes):

Grooves were etched out with a sharp blade, and filled with white paint:

The dragon models were modified to have a 2mm hole through the middle. The bottom of the dragon bases feature two “grippers” to ensure a tight fit against the carbon fiber rod:

And the dragon bases were modified to have 2mm holes for mounting the rods:

This alternative height system works nicely:

This design loses the discrete dragon facings of the previous designs, but the time saved when adjusting dragon height during gameplay is considerable. Although this height solution is not fully 3D-printable, it is still accessible thanks to the standardized 2mm carbon rods being readily available. Players can choose whichever system works best for their group.

In the above sections I’ve described the final decisions that were made, but it took 9 revisions to arrive at the current version of DragonWars. At each step along the way, the game was playtested with 2 to 4 players.

During the development process, a full manual was maintained, containing the ruleset up to that point in time. For each playtest, players were given a copy of the manual and left to read it on their own - this helped to clarify any confusing rules or poorly-worded sections of the manual. Games were played using the rules as written at the time of playtesting. Copious notes were taken during each playtest noting unexpected situations, rules that seemed unfair/incomplete, and any suggestions from players:

These notes were reviewed after each playtest and the next revision of the game implemented all changes which were deemed appropriate. In a few cases, rules were “rolled back” after a playtest if the change was found to do more harm than good.

I ended up with a balanced set of rules, detailed in a complete Rules Guide:

The dragon models could use improvement - it is still difficult to tell which direction dragons are facing, and the dragon models look awkward when they are in an elevated flying position.

Both of the height systems are quick to adjust, but the mathematics of height changes becomes confusing when a flying dragon moves over terrain that itself differs in height. The mathematics is simple in principle, but in practice it is confusing and easy to get lost as players are moving their 4 dragons amongst all the other dragons on the board. There should be a way to make this simple and intuitive - having a numeric height value written on the corner of each terrain hex might be sufficient to simplify the mental math.

Combat is still too punishing for inexperienced players who are not skilled at predicting the movements of other players. Too often a plotted combat action is forfeit as a result. I have an idea of abandoning pre-plotted movement and instead implementing “combat cards”. Specific dragon types would still be eligible for the same combat actions they are eligible for now, but each player would select a few of these combat cards (without revealing them to all players). After movement actions are completed, players could use their combat combat cards for any eligible dragons. This strike a balance between totally pre-planned combat, and the too-simple approach of allowing all possible combat actions each turn.

The default gamemode of “Capture the Egg” takes advantage of the terrain and is fast-paced and fun, but players may enjoy a more “dogfight-like” experience. I could add two additional game modes to satisfy these players:

I’ve achieved my goal: DragonWars is a fun, fast-paced, visually appealing convention-style aerial combat game, 3D printable by anyone at home.

A two-player game of DragonWars:

A four-player game of DragonWars:

You can obtain the latest version of the manual, 3D-printable files, terrain hexes, and everything else here.

If your group makes any tweaks or improvements to DragonWars, please reach out and let me know!